Why We Achieve More by Doing Hard Things and Not Easy Ones

We don’t grow by staying comfortable we grow by doing the hard stuff. That’s not just motivational talk, it’s backed by neuroscience.

As human beings, it’s natural to want comfort. We like what feels safe and familiar. But real growth whether in healing, recovery, or personal development doesn’t come from staying in our comfort zone. It comes from facing challenges, facing what feels hard, and learning to sit with discomfort. This isn’t just a motivational idea it’s something actually neuroscience supports.

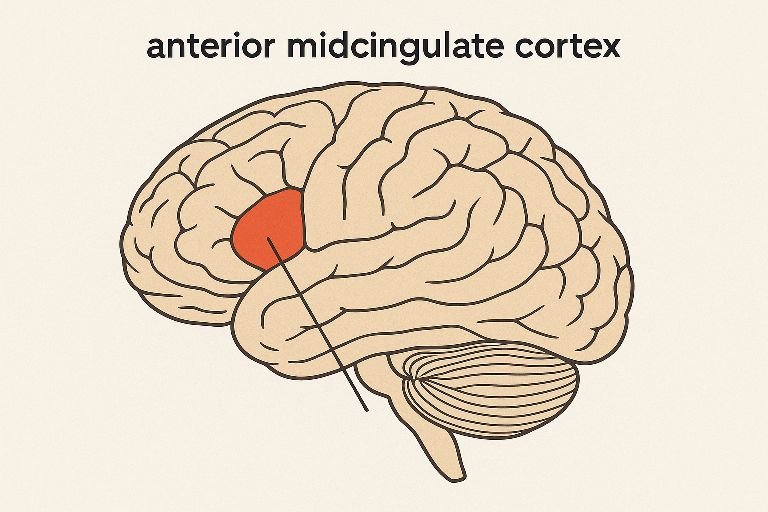

There’s a part of our brain called the anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC). This area is involved in motivation, effort and persistence. Each time we push ourselves to do something difficult, especially when it goes against our habits or impulses, the aMCC “turns on.” It helps us stay focused, tolerate discomfort and keep going even when we want to give up.

Take, for example, someone working to overcome an addiction or break a compulsive habit. Every time they feel the urge but pause and make a different choice, they’re not only showing self-control they’re strengthening the brain pathways that support long-term recovery and resilience. The struggle itself is part of the brain’s training, much like exercising a muscle.

Research also shows that people who consistently succeed in different areas of life whether in recovery, sports, work, or relationships tend to have a more active and even larger aMCC area. But here’s the important part. This part of the brain only stays strong when we continue to challenge it. Avoiding discomfort or difficult choices over time can weaken it, making it harder to manage challenges when they do come.

That means success or healing isn’t a one-time achievement. It’s an ongoing process of choosing growth over comfort. High performers and resilient people keep taking on challenges not because life forces them to but because they know it helps them stay grounded and capable.

So if you want to grow, heal, or move toward your goals, start small. Do one thing today that pushes you. Resist an old habit. Say “no” when it’s easier to say “yes.” Sit with a feeling instead of avoiding it. Each time you do, you’re not just practicing willpower you’re shaping your brain to support the life you want.

Growth isn’t easy. But it’s in that very difficulty that the real change happens.

References:

1. Shenhav, A., Botvinick, M. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2013). The expected value of control an integrative theory of anterior cingulate cortex function.

2. Tang, Y. Y. Hölzel, B. K, & Posner, M. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

3. McGovern, D. J., Polter, A. M., & Root, D. H. (2021). Neurobiology of drug addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis.

testimonials

Cristian's kind and empathetic nature always made me find our sessions a safe and happy place. I gained a new perspective on so many things that had been causing me anxiety by learning about the CBT framework of anxiety”

I have referred many people to York Region CBT - Cristian over the last year and would support anyone any parent who's child is dealing with OCD to make that initial appointment and start working with Cristian.

Cristian is methodical and will take you through the CBT steps without any judgment and drama so soon you will find new ways of looking at things in a different light without changing your personality or things you believe in.